“As a memory, however, it was already looking good.”

Annie Dillard, Aces and Eights, Teaching a Stone to Talk

When I was six years old, my Mom, my Dad, my brother and I lived on the island of Negros in the Philippines. My fair hair and light skin meant that I was physically as well equipped as a polar bear to live in the tropics. I spent my time playing on dirt roads with other kids from my neighbourhood, as goats and stray dogs wandered about. Other small children would often only wear a shirt, or sometimes nothing at all, and they had wonderfully demonstrative names. There were brothers, for instance, named Bong Bong and Pit Pit, the former of course being the older and larger of the two. We played “Kick the Can” together, which I remember involving a can, kicking it, and running around a lot, but other than that I don’t have any idea how it went. I attended an elementary school where I learned Spanish and Tagalog, and about a history that was not my own. The school was on the campus of Silliman University, where my father taught on sabbatical, and where he had resigned himself to the reality of trying to get lab equipment shipped into a country where corruption and payoffs were the norm. Ferdinand Marcos was still in power; “martial law” was the national political hue. Looking back on it, I’m struck by the fact that no matter how rotten that regime was, we were safer there then than we would be now, with the threat from the south of religious fundamentalism and national separatism. But I knew nothing about all that at the time. Customs told Dad that his beakers, tubes and Bunsen burners were clearly drug paraphernalia, but he could have it, of course, for the right price. Dad wouldn’t do it, and gave up being a research biologist for spending his time snorkelling amongst the corals and eating roast pork on the beach with a gang of fat, local businessmen. My Mom on the other hand took on the task of resupplying the island’s libraries with donated books form America (apparently not seen as potential earners for the customs officers). As for me, it was a sun burnt, bleached, rash-covered, mosquito-bitten, quinine-tasting time, but I remember being happy. Unlike my older brother, I was still at the age when the world just is what it is; I hadn’t learned to think, “wait a minute, this can’t be right, I’m a middle class American child, where are my TV shows and swimming lessons at the local pool?” I accepted, for example, that Santa’s sleigh didn’t make it to the South Pacific, when I received my bag of peanuts and some bananas under our chicken wire and tissue paper Christmas tree. It just wasn’t a problem, apparently. Had we gone instead to upper Siberia and donned giant coats with fur skinned hoods, it would have been no different: I guess life is playing in the snow, then, eh? But life was, for a while, that of a freckly, strawberry blonde child playing in the sun under palm trees. I can picture in my mind the school courtyard where we sang the national anthem every morning, probably because we have a group picture of all the students on bleachers in that very place. It isn’t difficult to pick me out of the crowd, the one sandy, melanin-deficient, bright white bleached Northern European head amongst the dark haired Filipinos, standing not far from my more fortunate brother, who had inherited the dark hair and ability-to-tan of our father. The hair became a problem at school when older children starting sneaking up behind me to yank it out in tufts, for souvenirs I guess. Parents were told, meetings happened, kids got in trouble.

I want to think about the past, which means thinking about the present. Over a pint, my friend M.C., upon me telling him that the past doesn't exist, told me that the present doesn't exist. My point was that all we have are things that are available to us in the sensory present, including our memories and all our other records. Memories and records are their own things, and are not actually moments of the past, because the only moment that we ever really have is this one, which is of course gone now, but it's OK because we have … this one … and this one (carry on, this sentence is a waste of time). All we can do is relive the past in the present, which is memory. M.C.’s point was that this moment is an illusion, not really here; that this moment we call now is really only the most recent history, and in order for it to exist it has to have already passed. As one approaches Now in their memory, one discovers that it has no dimensions, and is merely where Was stops and Yet begins. Cast your mind back to when you just read the previous sentence. Now try and remember when you started reading this one. Now: how soon is it? How long? A second, a half second, tenth, milli, micro, nano, pico? It’s a lit fuse, with never any boom!, a jug of water, poured into itself, eternally. M.C. was right: Achilles never did catch that damn turtle. In philosophical terms, it may be that he was talking about Now as noumenon (a thing in itself, distinct from what is knowable from sensory input) whilst I was talking about Now as phenomenon (a thing as it is experienced through the senses). OK then, I want to think about the phenomenon of memory, of past, of present, of time’s passing, and leave for another day the question of whether or not my cat and I (she won’t stop staring at me) are actually sharing this moment, or this one, or.

Do I remember having my hair pulled out, in as much as a memory can be entirely free from stories that are told to recount them? The story of the hair pulling was told time and time again to the old ladies at the Baptist Church back home in Danville, KY. The memory became a story in the early ‘80s. And yet, what is a memory but a story you tell yourself upon remembering? I suspect it is mostly just that. I remember generally that it happened, why it happened, who it happened to, when it happened, how it happened, but not, it happening. In reality, if I concentrate, the Philippines of my mind is vaguely sepia and accompanied by the sound of a slide-projector fan. I’ve been told that every day the bread man came on his cart I would pig out on bread, because it was that good. A middle class American six year old would have only ever experienced processed white bread in the late ‘70s. I apparently got a bit chubby after months of this as a result, which is funny. So it became a story. My Story! But can I in any sort of sensory imprint from the past reclaim the experience? The scent of the loaves, the taste, or the texture? Oh, it must have been wonderful, but it is as cold and dead as these words on the screen. I really don’t know if I ever tasted it. I simply can’t go back there. It makes me sad, because really it’s gone, all gone, into stories or lost forever.

And yet, very rarely, the perfect tincture of sensations – diesel gas, sewage, fresh coconut, sugared rice and bananas, and the immense freshness of photosynthesis en masse – throws me back into that humid crush of endless tropical summer, that exhaustive ubiquity of life feeding on life. It caught me unaware in Florence, Italy, once, in the mid ‘90s as I walked past a church on a hot summer afternoon. It was a time machine, and with the sensation came the unbidden sound of singing through the palm trees: This is my father’s world, and to my listening ears, all nature sings and around me rings, the music of the speres. For once I didn’t need pictures or stories for it; it might’ve been a memory! Just a memory. Recently I was in an art gallery that smelled exactly like my high school girlfriend’s house, and for some time I sat petrified, floating in a fog of memories: the record player in the corner, the black and white dog lying on the floor, idly wagging her tail, the low volume of some Joni Mitchell record. These occurrences are rare. Mostly my past is simply a ledger of known facts. The sensations of the past are rather harder to come by.

∞

The ninth commandment is, Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour. What about the guy up the street? Or historians? The composer Charles Ives seems to have lied about himself and his dad. His early life is a kind of black box, most of the evidence for which is derived from what he himself wrote about it, which can be found in the autobiographical Memos compiled by his biographer John Kirkpatrick. Almost all of his important premiers happened years after he wrote the music for them, and once people cared to hear the story, it was his to tell. He quite liked making it appear that he beat Stravinsky to the modernist punch, and that furthermore his father inspired the whole thing when he was a child. But hang on a minute, Charles, your old crony Elliott Carter lived for rather a longer time than anyone expected, and he says you did a hell of a lot of retro-modernizing of your scores, years after they were originally “written”, and well after the world of music had felt the impact of the early 20th century’s most significant modernist innovations. What’s the story, eh? (“Well, Drew, that’s it, that’s the story, as I have told it,” says the ghost.) Musicologists have since the 70's chipped at the old man’s suspect self-aggrandizing edifice to the point of collapse. Well then, Charles Ives' memory was a story he told us himself, and Maynard Solomon pointed out the danger this poses to veracity, working under the premise that such a thing is important.

Autobiography occupies a zone between self-discovery and self-invention, between the faithful reconstruction of the past and an imaginative reshaping of distant events to serve present needs. The autobiographical act is often a medium for reconciling conflicting aspects of the self; it is a creative process, and thus lends itself to revisionist pursuits.

Maynard Solomon, “Charles Ives: Some Questions of Veracity”, Journal of the American Musicological Society, V. 40, no. 3, 1987

John Kirkpatrick tried to put a forgivingly cultural hue on what might otherwise be considered garden-variety dishonesty. "It's not that you can't believe a word he says because he was a liar. He was not a liar, but he had a very sly sense of humor and a very acute New England sense of privacy, and often he'd just throw smoke in your face". Or to put it another way, It's not that you can say that he's a liar, but he did, you know, lie. He lied! He cooked the books so he’d come out ahead. He bore false witness and told a story about himself. But is it so wrong? Is it anything I wouldn’t have done, or indeed, could be doing right now? The truth of my past can only be found in amongst the reality of it; every fact taken out of context, every simple verity amputated from the life I’ve lived. All these facts feel like a big pile of So What?. Thou shalt not bear false witness. I don’t get it; we’ve just got to follow these steps, Moses, that’s it? Seems too easy. Maybe that’s why the Catholic Church did so much to flesh out just how deliciously rotten we are in our falsehood. To bear false witness is nothing; but we tell envious lies, greedy lies, gluttonous, pride-filled, wrathful lies because we’re too God damned (literally) lazy to tell the truth. These are lies of a deeper human quality, for sure! I am lying to you right now, in these paragraphs: the sin of pride. But isn’t the territory occupied by one’s past always to be viewed through some kind of spyglass, whether it be of pride, of shame, of sentimentality, of nostalgia, of horror, etc? Isn’t there at the very root of the dialectic between self and consciousness something of a lie? I’m lying right now, but if I’m going to talk about myself, it’s the only way I know to tell you the truth.

I might ask, “Charles, you sad old man, why did you lie?” But I don’t care: there’s no Rite, or Pierrot, nor is there any aria, no Eroica, no White Album, no Passion, no anything under the sun, that makes me feel like my recording of his 4th Symphony. It’s just like that particular summer view across the forested Appalachians, near enough to his beloved Danbury: every-blue, layer upon layer, lighter and lighter, to the horizon. And then: sky. Ives said, “Music seems too often all foreground even if played by the master of dynamics.”

I need this tale of the past, just like Ives – not the record, the hard facts, but the story. And my need of it is not what it is, but what it is becoming, so long as the fuse is lit. My Now and my Then proliferate together, feeding one another, until I am done. I have another memory of a little me at naptime, bundled up in a crib in the late 70’s beneath the window in the back room of my Memi's house in West Kentucky. It must have been a few years before we went to the Philippines. I was gazing through lace granny curtains in gothic half-light listening to the thunder rumble, and then gradually to a sound stirring through the open window that poets always fumble to describe (I think e.e. cummings wins with “the great dim deep sound of rain – of always and of nowhere”.) I hung in limbo between the chrysalism of bed sheets, warmth and rest, and the jolt of life that straightens your back, stands you upright, face to face with the cold rain and electric violence of nature. If we should approach our graves, as William Cullen Bryant suggested in Thanatopsis, “Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch about him, and lies down to pleasant dreams”, then maybe we ought to approach our lives as just this in reverse: To Wake Up! like John Cage said, “to the very life we are living”. Throw off the duvet! Feel it, really sense it, in every way. Throw off the covers and feel the cold, stand in the rain, and shiver. I didn’t think any of that at the time, how could I? But there it was, and still is to this day: a pebble that started rolling, picking up momentum, and there is no record that can account for what it became. A few years earlier in 1974, I lay in my mother's arms in our home in Danville, as one of history's largest tornado outbreaks swivelled through the Bluegrass, dropping 148 twisters in a 24-hour period. I can't have remembered this; I was exactly one month old. But now I do remember this. From the stories of my parents, I have begun the story of myself at this point in time, wrapped up, quiet, not comprehending that sky full of fury, naked of all hope for myself, a nobody, a cypher. Thunder rumbled, the sky churned up, lashed the land, twisted the trees, and I came into the world. I’ve always loved these storms that awaken in the springtime. They are accompaniment befitting the person I was to become, so say I. But the record shows that mine was a planned C section, that it all actually started for me in the antiseptic light of a hospital room, faces half-covered, the world half felt on entry. I hate that story, so I lie. Time and time again across the expanse of undifferentiated Nows, I think, is this not a good start for me, in the storms of 1974?

∞

Do you remember 24 hours ago? What were you doing? I actually don't remember it at all. I know because of my habits that I was likely either hanging out with my son while he takes his bath or cleaning the kitchen up after dinnertime. It makes me so uncomfortable to think about it; where does Now go? And there it goes again, into a memory or lost. What about a year ago? Tell me of three memories you have of 2013. Don't tell me three things you did, like getting married or having surgery or quitting your job. These things are all very well documented, I'm sure, in some medium. Tell me three memories, felt, in the Now, from any part of your life. When was the first time you were truly startled by a kiss? Can you feel that? What about looking at a loved one who is dead? Surely that’s a unique experience. Describe for me one chain reaction of unendingly complex synapses that constitutes a re-emerging of another sensory Now. Can you?

I can! There’s only one thing I can remember consistently. Around 1990 I fell backwards while trying to climb onto the roof of a friend’s home, landed on my legs oddly and dislocated my left kneecap. I am squirming writing this now, because I can still feel it in my mind. It was the most singularly exquisite pain I have ever felt in my life, and a guy name Sean laughed at me as I shouted out. Now, 25 years later, I reach for my knee and wince at the feeling of it, the memory. But it is oddly comforting. It was me, that spotty, awkward, so-lanky-that-his-bones-can’t-hang-together teenager. It was my pain, it was me! I can feel it, I remember.

We think of time as a road, a line behind us. Here’s another model: Now is stationary, at the centre, the past recedes in three-dimensional waves in all directions. It’s a better model, this radiant time, no? It certainly locks in better with the way the universe has begun to unfold since the time of Einstein.

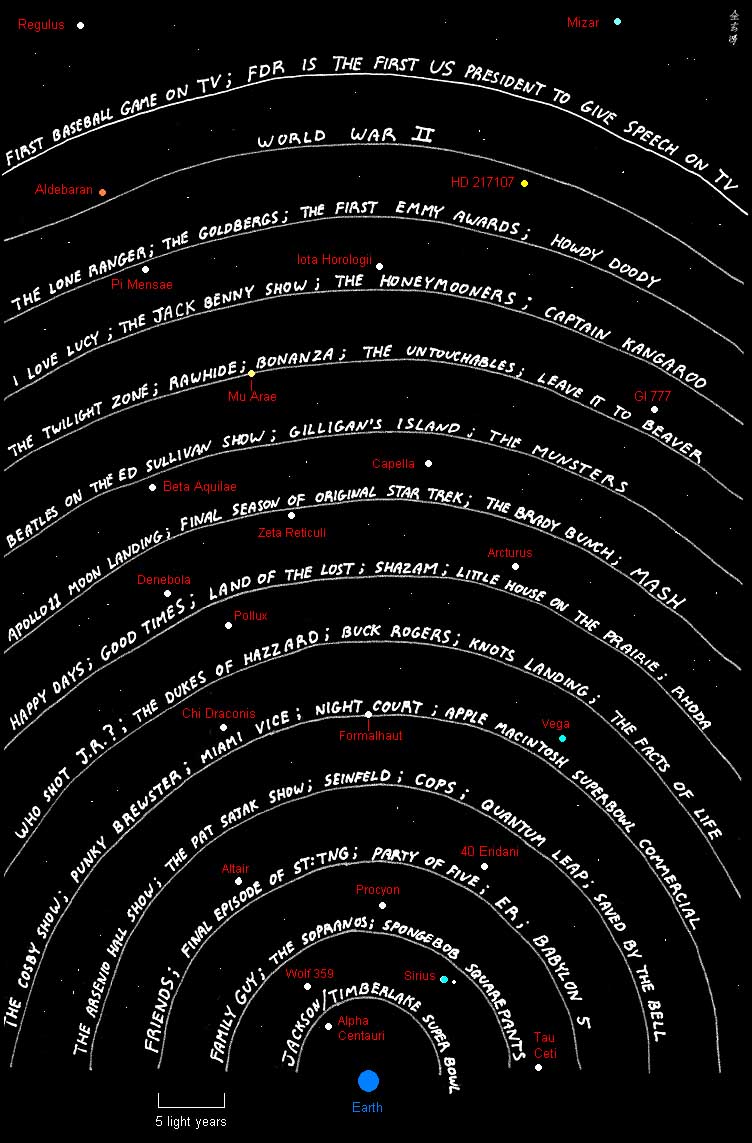

This picture from zidbits.com shows where our radio transmissions have got to in space.

I like the idea of Clayton Moore as the Lone Ranger riding proud past Pi Mensae or Iota Horologii some 60 odd light years away. All of our culture, our immaterial glory, pulsating across the galaxy! Henry van Dyke’s mighty ship, sailing beautiful and true over the horizon, beyond our feeble, corporeal sight! My radio show at WQFS in the mid ‘90s, "Jazz on a Sunday Afternoon", has already met Alpha Centauri and Sirius. It’s glorious! And a fantasy, of course, due to something called the inverse square law, which basically means that all Earth-based radio signals become indistinguishable after about two light years. Does nothing last? Is that van Dyke-ean vision all just a comfortable sadness, by and by Lord, by and by? My Memi said that they'd have to shoot her on judgement day, but after 103 years, she was wrong. She died. Though of course, she’d have told me differently! For her the ship sailed on: For God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life. But for me, I think King James' team of translators didn't get it: everlasting has the exact dimensions of neverlasting. Time is duration. How can it be otherwise? But whoever first penned the apokalypsis knew well enough: there should be time no longer! Now that’s something worth thinking about. No Time, no Memory, now Now, no Then, no Yet to Be.

∞

Music is a beast to get your head around, it must be said. I ask my students to describe for me the difference between the experience of music and the experience of painting, sculpture, etc, beyond the fact that you listen to one and look at the other. I can find no better answer than the way it is with time! It’s all about time’s radiation. Sound is the phenomenon of time’s radiation made explicit, and cannot be otherwise. But what about the moving image? Well, when you pause a visual recording, you see a picture. But when you pause a sound recording, you hear no sound from the recording. We have nothing in sound that is completely analogous to that kind of stasis. Sound is always alive, shimmering, playing right on the edge of M.C.’s noumenonical Now, and so music must be too.

Or must it? I find myself thinking of all the ways that we talk about music, as time-constrained organised sound, as social or cultural construction, as dictated by subject and intention (Thoreau: music is constant, listening intermittent), and I fear to try to reduce it. Again, there is the noumenon, but I want to think about the phenomenon. As I write, my mind follows almost subconsciously the thread of "Reflections" by Thelonious Monk. It is, simultaneously; a hue, dark as treacle; a texture, wooden and resonant; it’s the proprioceptive solidity of fingers on keys; my high school-era basement bedroom in Danville; it’s a sequence of abstract relationships – chords, melody, etc; a collage of colour; a simple, sweet, soulful sound beyond all this description. It blooms, “heard” in my mind, but it doesn’t occupy time in the same way as it does as listen to a recording, or as I play it myself at the piano. Simply put, there are two things here that I can detect: the piece, and its realisation in time. In sum, it, it’s totality, it’s gestalt character, stands outside of time as a constellation of thought, irreducible. “I know that piece” refers to something different than “I heard a performance of that piece”. I understand what it is, when taking the reality-through-a-lab reductive approach, but that real is always found in amongst complexity and chaos.

I explore with students Messiaen's Quatour pour la fin du temps, not only to get them to see how the composer used time, but also how he didn’t, and how others have obeyed a strict and insidious attitude of linear time, indeed the extent to which that attitude has defined what we broadly call Western Culture. But I think Beethoven had cottoned on on to something big a century before Messiaen. It seems he knew that variations drew a line into the past, and that's why he dwelt on them at the end of his life. Time had come, as they say. A set of variations is the most suitable analogue for the time it occupies; it both takes time and is about phenomenology of Now and Then, which is memory. In the kernel of Now is encapsulated the spirit of Then, and thus the extraordinary capacity to engage emotion through the alchemy of the remembered and the new. But it is all beautiful desperation, isn’t it? He must have known that it was ultimately for nothing (Muß es sein?), that these utterances, however captured and glorified since, were also the fodder of oblivion (Es muß sein!). Beethoven lost the thread in the second movement of Opus 111. The variation form disappears, becomes subsumed under invention. In writing, I think he knew it. I think at that in moments like this, in music, he was free. When pressed about the oddity of only having two movements in the sonata, he famously said, “I did not have time to write a third movement.” No time. But what else was there after that? How can that sonata have not said all it was ever going to say? Beethoven went through the variations and found himself on the other side. That’s my theory.

One time in a lecture about Stockhausen and moment form I, as violently as I thought I could get away with, kicked over a desk. HA! I made my point, as Stockhausen put it, “the minimum or maximum may be expected in every moment”. Then a student, who was quicker than I (most of them are), said, “well, you are talking about moment form.” Dammit. It was a crude thing to do, and I am reminded from it the difference between random and “random”, the latter being a flippant, subjective reaction to that which falls outside of one’s own self-limiting attitude. Basically, it means the same thing as weird. (OMG, that was so random!). John Cage understood the necessity to be disciplined in order to be truly random, in the same way that a scientist must be disciplined to do what they do. Otherwise we’re kidding ourselves. How can I do anything at all without unknowingly continuing my same old story, locking right into my old pathways of selfhood? The baby of storms, the blistered child of the tropics, and all that? I have to be systematic, to force myself to be quiet, to let go of my longing to climb back into my serene repose of aesthetic judgement. I can put it another way too: I have to be disciplined in order to truly forget the story. This is the very moment when variation becomes invention. The moment to be that child I was, so that once again the world just is what it is.

But now I’ve left the past and memories and all that. I’ve left Was and turned my attention to Yet. The story of myself looms, like a congenital chronic condition, always there, always me, predictable and humdrum. A warm bath, a thick duvet, goodnight, rest in peace. But what about this, the trickiest of my objects: Yet? I remember long ago a conversation with another friend, M.D., in a red pickup truck, in the rain, on some interstate highway in America. We both came to the definitive conclusion that we were not the kind of guys to hang about with our shirts off, unlike some other friend of ours. Furthermore, and most importantly, it was self-evidently and undeniably true that neither of us could simply decide to become the kind of guy who hangs about with his shirt off, because, well, we never did say because it was so true! It wouldn't be the first time young men have mistaken agreement for objective truth. I attend to it now because it shows just how much we spend our lives going over the lines of a picture we finished drawing years ago, and for what? What does it do for anyone? As an artist, it is paramount that I have the discipline to bring my delicately crafted self in direct conflict with the chaotic environment, to understand that this self ossified out of the randomness, and will return to it in time. That’s the drop of magic potion for me, the thing that makes it all work.

“Know thyself”, so says the Ancient Greek maxim. Fine, I suppose. But it reminds me of a take I heard once on the Cartesian Cogito ergo sum: I think therefore I am… what exactly? Thoughtful? A bad person? Ecstatic? Miserable? What’s really important here? “Know thyself.” I figure this asks for similar completion. Know thyself to be as ephemeral as you are robust, to be just like Heraclitus’ river. Know thyself to be irreducible, to be a collection of thoughts, a big hunk of meat, a story, a set of relationships, a set of potential actions, a talisman of another's dearest hopes, all at the same time. Know thyself so you can be courageous enough to forget thyself when it is important to do so.

∞

Last night I dreamt of my home. Not one of my homes, not a particular place, but my home more in its essence, a state of being all my homes and none of them, all at once. My Now, my Then, my Yet. It was a multidimensional collage, frozen in time. It was Dennistoun in Glasgow; South Boston; the Bluegrass; Silliman Village, Dumaguete City, Philippines; the Red Clay of Greensboro, North Carolina; it was my parents; my primary life; that incisive awareness of home; which I can only definitively describe as the place where there once was no time. Most important – I can’t stress this enough – is that in my dream I had left it. It wasn't a just place I was in, but a place I'd gone back to, invaded. A place had opened up between my here and its there. There was a wedding there, and I apologised to the hosts for my intrusion. On the wall was hanging a dress from Thailand that my mother used to wear, and that my wife still wears from time to time.