Episode 1, 1987

Zero Hour, Home Room, Bate Middle School

1987 isn’t the first year I thought about music, but it is the first time I have a specific memory that ties the music I thought about to a particular year. It was in my 6th grade homeroom class in Bate Middle School. I remember clearly a discussion between LaChrista B, Hunter P, and I, about the relative merits of The Jets, Duran Duran, and A-Ha, respectively. I wonder what my classmates think all these years later. Do they still listen to the bands? Do they even think abou them? Duran Duran are obviously the most pervasive and successful of these three, having now in some form made music for 40 years, which is just nuts. The Jets are this effervescent Polynesian Minnesota band (God, I love America) that lined up a few chart toppers, namely "Crush On You". Ha! Remember that? The funny thing about all three is that, even though ostensibly they were from differing genres, they provided quintessential examples of the kind of pop production that emerged post midi standardisation and digital synthesizers. This sound permeated my childhood.

Now, in my mid 40s, I’m left in the slightly odd position of presenting some kind of coherent perspective on A-Ha, a band that was clearly at best a one-and-a-half hit wonder, the half being that one about sun always shining on TV, the other one being, well, you know: doof tick biff tick doof tick biff tick doof tick biff tick doof tick biff tick bliiiiinggg – brwow brwowwwwww – bedank donk bedadank d-donk bedank donk bedadank d-donk … you know the rest.

But here’s the thing: I don’t need to justify my childhood appreciation of that brand of manufactured, sickly sweet music. Popular music doesn’t have to be “good” to work, it just has to work, and sometimes I think my own adult critical apparatus just clogs up any genuine experience of it. A-Ha? The first time I was ever struck by the beauty of an oboe was Claire Jarvis’s (I hope her ears just started burning, oddly) playing in "Living the Boy's Adventure Tale". I listen to it now, and I’m immediately split. Half of me is a cringy adult thinking, what an absolute stomach-churning glut of depthless musical pudding! The other half is an 11-year-old boy hiking on a mountain in Tennessee with his dad. That experience is real, it has impact. I should pay attention to it.

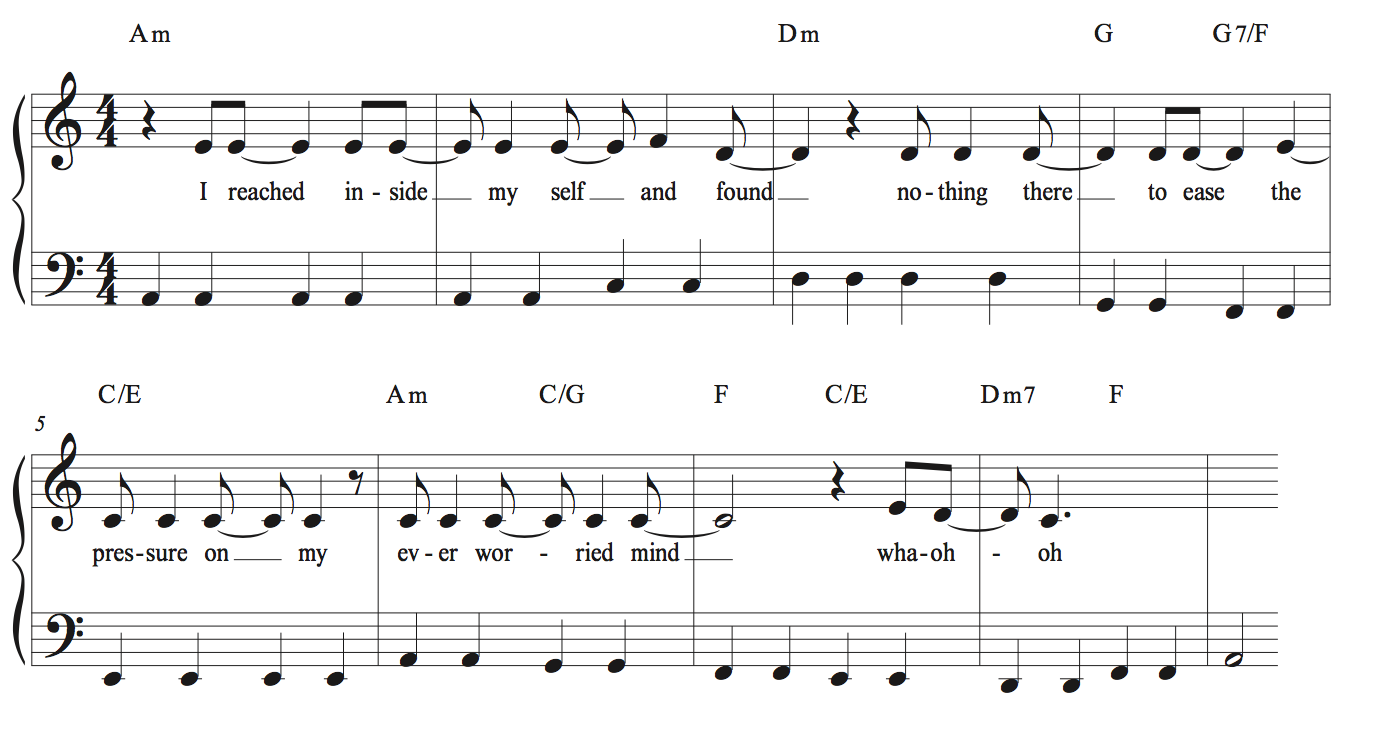

I also have come to believe that learning about the mechanics of music doesn’t always require the towering masterpieces of the Western Canon. The depth of engagement with whatever you’re interested in is far more important. I’d have plenty of time later to explore the be-wiged greats of the past, but the first time I really became interested in a harmonic progression was with “The Sun Always Shines on TV”. There’s a first inversion C major chord on the word “pressure” in the first verse, and a first inversion major 7th chord on “touch me” in the chorus. And touch me it did, folks [ohhhuuggh dryheave]. I was captivated by it, and on figuring it out I came to recognise for the first time the importance of line, especially in the bass, and even if I wasn’t able to articulate that realisation as such at the time. The bass line generates forward motion though inverted versions of chords. The inversions aren't there to merely sound different – they contain no real impact in themselves – but they preserve the line. Oh, nice. These revelations, unthinking, prelogical, were extraordinarily formative. The verse really is quite a good little passage. Here, in a simple two-part texture:

Those ’87 LPs

So, I want to present a perspective that doesn’t trade in any ultimate qualitative rules for pop music. In a sense it is a personal memoire, but one that tries to look at my experiences with pop music objectively, without clouding it up too much with qualitative judgements. Autoethnography, to use the conference paper term. I went through phase after phase in my late teens/early 20s, each characterised by a certainty that I had found my music. By the time I was getting into punk, everything that was not punk and that I had at one point loved when I was younger was only worthy of contempt. Noodly happyish deadhead music, grunge, classic rock, showtunes – these were all musics that I, as a 19 year old, would have felt shame at once liking. I was aspirational in my taste; I had to prove my cultural mettle, as it were, which is no doubt connected to living in the high-cultural desert of small town Kentucky. Punk worked because the music was quite often about a sense of cultural superiority through countercultural otherness, and similarly my budding excitement about cerebral jazz and classical musics played to my sense of educational superiority. As a teen I even abandoned the Baptist Hymnal for the proper, buttoned up, Anglican Church music with my move from the Baptist to the Episcopalian church, although that was mostly about girls.

It is interesting that in the mid-to-late 80s, before music had any connection to my identity, my tastes were stylistically disparate, more like they are now. I know now that this is the way it should be for me – I want to hear as much music as I can hear, and my identity is more complex than what essentially comes down to a consumer choice. Music doesn’t seem deeply connected to how I feel about who I am deep inside, or whatever, beyond the fact that a lot of it is just really interesting. I’m not saying I don’t hear beauty in music anymore, or that it doesn’t move me, but rather that the style element is simply not connected to my sense of self in the way that it once was. I think this is the right musical ethic to have, but I didn’t understand that as a psychologically tempestuous teen, and as a kid, I didn’t, er, understand that I didn’t understand that. Let me try to make that even more confusing. I had not yet learned that music really should be ruthlessly tied to your sense of identity, which is good because it really shouldn’t be, after all. You feel?

Albums I knew well before ’87 – prestylistica:

- A-Ha – Hunting High and Low. Already mentioned, and the next album, Scoundrel Days.

- Bon Jovi – Slippery when Wet. (eww) It was all about that Richie Sambora talk box guitar intro in “Livin’ on a Prayer”.

- Lionel Richie – self-titled album. I remember stripping paint off the walls of my house on East Main Street, inhaling questionable fumes, and singing ‘you are the sun, you are the raaaaainn, that makes my life a foolish game’ at the top of my lungs.

- Michael Jackson – Thriller. Watching Night Tracks in Sean S’s basement.

- Credence Clearwater Revival. I think it was one of those mail order retrospectives. I blame Dad.

- Prince – Purple Rain. dook knok knok dook… dook - knock dook

- Madonna – Like a Virgin. Mom, what’s a virgin? Is that like Jesus’s momma?

- Def Leppard – Pyromania. What do you want? I want rock and roll, you betcha... Not the only quintessentially American band from my childhood that turned out to be English.

- The Pretty in Pink Soundtrack. This in a sense forms a stylistic template of the kind of thing I’d be into in a few years. That OMD song was a last chance saloon for the pompadoured 80s revival of 1950s America. So was Duckie.

Albums I knew very well in the late 80s. It’s all about 1987, which was a banner year in popular music. Each of these were released in ’87 or ‘88. buddingwhiteboybaltandbritrock

- The Replacements – Pleased to Meet Me. These tracks accompanied my budding attempts at the guitar.

- R.E.M. – Green. (in 88, and Document, the year before) Ashley and I still sing You Are the Everything sometimes at bedtime music time.

- They Might Be Giants – Lincoln. The happiest, saddest band of all time. All sunshine, ice cream and darkness.

- Guns ‘n Roses – Appetite for Destruction. No album in the history of pop music is better for cruising the Danville Cinema parking lot in a pickup truck.

- U2 – The Joshua Tree. Partly chimed in with the fact that my grandparents had retired to Arizona, because, you know, Joshua trees.

- The Smiths – Strangeways Here We Come. I should point out that the compilation release Louder than Bombs was released in the U.S. in ’87, which was probably a lot more important to me personally.

- Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason

- Echo and the Bunnymen – self-titled album. Though again it is probably as much as anything to do with the Laurie Latham production of Bring on the Dancing Horses, which was known to me through the Pretty in Pink soundtrack mentioned above.

- The Cure – Kiss Me3. This album was the best thing for unrequited ‘tween love. A thousand wasted hours a day, just to feel my heart for a second.

Most of these ’87 bands were mainstream, internationally, with tracks charting in Britain and America. This is interesting from the American perspective because at the time The Smiths seemed a wee bit fringy. I had no idea that Strangeways had three tracks that made it to the top 5 in Britain, and I was similarly clueless about Echo and the Bunnymen’s success in the UK. The Replacements and They Might Be Giants really are the exceptions. I became aware of the former because of mix tapes made for my older brother, which I’ll discuss in a moment. I’ve no idea how I got into TMBG, but I think it maybe had to do with my friend Mark F, who in middle school introduced me to the album Lincoln. There was a theme to these interactions. Someone like Mark would introduce me to a band and say something cool and reserved about how they like this or that song on the album, I would go away and listen to that album, and collect all the other albums, and become obsessed over a period of a year, and return to the friend hoping to find a soul mate who truly understands the music and discover that they stopped listening to them ages ago. I was a wee sad-o so I was. My dear childhood friend, Hunter P (of aforementioned Duran Duran fandom) resisted the brunt of my childhood mania over Appalachain mountains and their elevations (yep), when he and his two brothers staged a sort of intervention. "Listen, we need you to shut the fuck up about the mountains already, cool?" Now, three and a half decades later, I can still rattle off the top ten Southern Sixers and their elevations. What are brians for, after all? I suppose the question isn't so much about why I had so few friends as a kid, but why I had any. : (

Haha, whatever, I was a happy kid. Jim C (you’ll never read this, but if you do, Hi Jim!) made mix tapes and recorded albums for my big brother, Jason, who was not interested in them because they got in the way of him excelling at everything. Let’s do this rabbit hole, shall we? Jason was in every way better than me at everything he ever did with exactly two exceptions: one, not being severely stressed out most of the time, and two, music. I feel confident that if he had cared he could have excelled in music too, but he didn’t care. He left Jim’s tapes for a young me to discover on my Sony Walkman all by myself. I was, well, captivated, yes, but my obsessions have always been strangely characterised by a certain detachment, just like those mountains. It didn’t feel like I loved the music. It felt like listening to music, and trying to play it on my guitar, just seemed like the best way to spend my time when left up to my own devices. I just felt kinda compelled.

I can remember one instance later in my adolescence when I was sitting at my piano playing a tune by Cat Stevens (noodly-happyish-deadhead-hippy-music-adjacent phase) and my grandmother edging her way into the room without me noticing. She sat there, enraptured in the way that only grandmas can manage, tears rolling down her face, clutching her hands in a kind of Mothertheresaesque pose, before I turned to notice her. I was appalled. I wanted to say, NO NO this isn’t for you, I’m not trying to move anyone by doing this, I’m not searching around in my soul for some kind of beauty in a hard and dusty world, it’s not some sort of Hallmark card situation. I’m just a creature of habit who finds this stuff oddly fascinating. Still do, really, only now I get a pay check to tell people about it. Life is weird.

Anyway, I don’t think that it is an overstatement to say that Jim’s tape opened a wee door for me into a world of music that wouldn’t be found on Central Kentucky’s FM 94.5, 98.1 WKQQ NINETYEIGHT POINT ONE, DOUBLE Q [wrestling announcer voice], or 102 JAMS. Therein I was introduced to, most notably, The Replacements, which led me in the direction of other Midwestern post punk world of Hüsker Dü, Sugar, Big Star, and eventually even to the post-post punk regions of country music, ‘cow punk’, etc. But that would all be later, in the 90s. By the end of the 80s my family had acquired a Sanyo hifi system (I have a weird memory of praying about it at the dinner table, “Lord, please bless this family purchase and help us to use it to further glorify Thy Name…”), and I followed up by buying my first LPs and 7 inches down at the Record Ranch in Danville, KY. (I have an oddly specific memory of R.E.M.’s single, “Superman”, with the drawing of the baby on the cover. Sorry, I feel like I use parentheses as a copout alternative to actually being able to write clearly. Anyway, what a truly excellent track “Superman” was for a kid who’s only learned two chords on the guitar. After an intro with both E AND E7, the progression goes, E, then A, then E again, followed by A, then back to the E, and, you guessed it, A. Later it gets more complex and ads a G. This neue Einfachheit was even more pronounced in R.E.M.’s cover of “Strange” by English punk icons, Wire. Musician’s baby steps.)

Letters and numbers: U2 and R.E.M.

In those ’87 LPs, I don’t think I’m wrong in saying that the overarching theme here is the idea of moving on, moving through, departure, etc. R.E.M. and U2 were at the beginning of mega-stardom, the former moving from the relatively fringy IRS (on Document) to the giants, Warner Bros (Green), the latter having recently come off successful album that had redefined the ways the group sounded. 1984’s The Unforgettable Fire was U2’s first collaboration with producer Brian Eno, and therein that bubbling delayed guitar sound from David Evans (I’m sorry, even as a kid I felt embarrassed about their stage names. I don’t use them) first came into its own. Evans had certainly found a delay pedal before then – just listen to tracks like "New Year's Day" from the album War – but it hadn't become quite the defining feature that it would over the next three albums. The delay, with that infinite guitar prototype he was using on Joshua Tree's "With or Without You", I don’t think is as acknowledged enough for its influence on later music, as can be found time and time again from Coldplay’s Johnny Buckland to Walk the Moon’s opener in the 2014 summer jams hit Shut Up and Dance With Me.

My relationship to the music of U2 is a telling one. I hate them, and I SO LOVE them. I can’t help it, I’m complex like that. I get it, these irritating megalomaniacs write the worst kind of preachy neo-liberal soundtrack music with an awe-inspiring degree of self-importance, and even as a youth it wouldn’t be long before I gained more of an appreciation of the likes of Negativeland’s mock EP on “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For”. BUUUUUUT, they (and Eno) gave me as a wee 14-year-old boy the opener of “The Streets Have No Name”, which I still find a truly evocative moment of pop musicality. There is so much there. The simple, four-note guitar line, transformed with that quantized delay into a kind of epic atmospheric that I found totally enveloping. And the organ part, well, I can only say that if you want a clear and succinct lesson on the workings of tonality, look no further than those resolving tritones. Listen up, kids. Tonality isn’t about a status of dissonance, but the treatment of it in time (D. Hammond 2018).

In the case of R.E.M., Document left behind some of the aspects of the Athens underground sound in favour of something more likely to be played on WKQQ NINETYEIGHT POINT ONE, DOUBLE Q [again with the wrestling announcer voice]. It’s hard to even think that tracks like “It’s the end of the World as We Know It”, or "Finest Worksong" are the same band that gave us the album Murmur. Yeah, yeah, I know “Radio Free Europe” would be a stadium rock song if it was just produced differently – it certainly sounded that way live – but that’s kinda the point: it wasn’t produced that way. It’s got some of the hallmarks of radio-friendly pop, but the sound just isn’t as expansive as what you’d get on NINETYEIGHT POINT ONE, DOU… ha, sorry, I’ll stop that now. Earlier 80s R.E.M. also engaged with a kind of quirky, found object, sensibility – who uses harmoniums and harpsichords in rock and roll? From Document on, R.E.M. got all cleaned up presentable, the snare sound got that clichéd gated verby thing, and vocals were often double tracked. These kinds of things define pop music production. Oh, and Mike Stipe’s lyrics became vaguely comprehensible. A year later we got the Warner Bros release, Green, with that song about standing in different places and facing cardinal directions. It wasn’t as sickly sweet as “Shiny Happy People” which came out on the Out of Time album a few years after that, but it opened the door. That pop song was poppier than Elton John’s and Madonna’s love child eating a lollipop dipped in an ice cream float whilst listening to the Beach Boys Greatest Hits. I’m proud of that simile.

I knew the Green album upside down and backwards. I was once, many years later, talking to my friend Katy C about the band and she said something like, “I don’t get why people like R.E.M., they’re very, very boring.” I don’t have a really strong retort to that. Some of the tracks on Green are positively anaesthetic in their emotional affect. The most remarkable thing about “Orange Crush” is that there is nothing remarkable about it. BUT, “You Are the Everything”? I don’t think I have before or since heard a track like that one. Everything about it just fascinates me: the song somehow manages to be played fast, but sound slow, and lyrics like “voices talking somewhere in the house late spring, and you’re drifting off to sleep with your teeth in your mouth” are just so damn evocative of something particular and universal at the same time. The funny thing about R.E.M. is that they didn’t really spawn pop R.E.M.-lings to the same degree as U2, although their earlier legacy informed the quasi-intellectual college rock type sound that would eventually cough up NPR perennials like The Decemberists, but you never got R.E.M.’s version of U2’s Coldplay (Pearl Jam’s Creed? LOLZ).

The Martin Stinger Years

Speaking of influence, I don’t think even now people have come to terms with the importance that the arrival of Guns n Roses had on The Great Haircut of 1993. Yes, I know Grunge had much more direct stylistic predecessors, and I’ll talk about some of them later, but I think it was important at that time for a west coast hair metal band to take the music past the eyeliner-and-spandex era. And it wasn’t just the look, it was the playing, and Slash was the key. (Slash parenthetical: don’t ask me why I’m happy with “Slash” but think “Bono” sounds dumb. Maybe it’s because Mr Hudson seems a much more likeable person. Also, a deeper parenthesis that I won’t go into here is the fact that in Slash we find one of the finest African American guitarists in 80s/90s pop music, but isn’t regarded as such because of the weird and complex way that race and identity work themselves out. Another day.) Compare the bluesy, valve-driven warmth of, well, basically every guitar track on Appetite for Destruction, to the Ratt/Cinderella/Dokken/Poison/Warrant/Skid Row versions. I may be alone in this, but I’d count Mick Mars from that band with the umlauts as a step above the DeVille/Sabo ilk. It’s ultimately about melodic form, and the lack thereof. It is interesting to me how much the difference I’m referring to is closely related to how the pianist Bill Evans spoke of jazz improvisation a few decades earlier; it’s the idea of “approximation” (Evans’s word), in this case of melodic form, that permeates the eedly eedly solos of glam metal.

Slash’s sound on Appetite gives evidence of a melodic blues/rock lineage that places it in a tradition from Muddy Waters to Jimi Hendrix, which of course ties it in essence to the human voice. Let me be clear that I don’t think Slash is as important or as good as the likes of Jimi – I doubt he’d make that claim either – but I do think that a greater depth of blues/rock history being brought to the forefront of pop music at that time did have an effect on the increasing retro-consciousness of late ‘80s American pop music. Well, affected, or was affected by? Likely both? Compare the swagger of the “Welcome to the Jungle” solo:

to the squealy nonsense of Scotti Hill’s solo on “I Remember You”:

It is interesting to me that Skid Row’s debut came out over a year after Appetite, which suggests to me the robustness of that shiny, late glam-metal sound. But the times they were a changin’, and five years later we had Nirvana and Pearl Jam.

It was during these late 80s years when I started, to my parent’s bemusement, showing an interest in expressing myself musically (I always hated the idea of “expressing myself” – brings to mind going to the toilet, but with emotions instead of wee. I don’t have a better way of putting it.) I had been taking piano lessons for a few years, and I had sung in church for many years; this was different. I was taking the initiative, figuring it out for myself. I’m not an outstanding musician, even now. I do some things well, and the things I know, which don’t amount to much, I know them better than most people know anything. Refer back to comments on my obsessive nature in childhood. I think this derives from this obsessively constructivist attitude about what I do, peppered with not a small amount of self-consciousness. Just leave it to me, I’ll sort it out in my own time. I am a composer who has never really been given anything that could reasonably be called a composition lesson, which is ironic given that giving composition lessons is what I’m largely paid to do these days. Sure, I spent plenty of my PhD days having excellent and extremely useful chats about music with my advisor, Bill Sweeney, but his interventions were never particularly instructive, they were simply what people who are enthusiastic about music talk about. He noted at my graduation that all he ever did was say, “sound like you know what you’re doing, carry on!”. Maybe that is what teaching composition often is, coupled with, at times, “you don’t know what you are doing, maybe you should try…”.

My go-it-alone mode of working showed itself very early on. When my folks first bought me a Martin Goya acoustic guitar from our wee music shop, I gave it one strum and though, well that sounds terrible. So I retuned it by ear until it sounded right, then got down to business learning by ear as many tunes on it as possible. It wasn’t until months later when I took it to church camp and a counsellor asked me if I always played in ‘open E’ did it start to make sense why what I would soon come to know as the A, D and G strings kept breaking all the time: that’s not the way guitars are tuned, dumbass! (I also quickly got very good at changing guitar strings.) So I went back home and relearned the guitar correctly.

It soon became evident that my parents sending me to my room was in no way a punishment anymore. I spent hours, and hours, and hours, listening, playing along, playing back. Once I got Mr-Successful-Pants Jason out of the house an on his way to becoming a Navy pilot, that Sanyo hifi was all mine, baby! I’d also acquired, from my dad’s hordes of 80s electronic gagetry one of those rectangular tape players with the single speaker (Dad was a Ham Radio operator – dads are such dorks. I guess that’s me now). Single speaker, yes, but RCA STEREO OUTPUTS, sweeeeet! With these playback and recording tools, my shiny new (crappy and hard to play) Martin Stinger guitar, a Casio CT series keyboard, and one of Dad’s kindest and most fortuitous purchases for me, a four track Realistic mixer, I “invented” multitrack recording right then and there. That is to say I discovered – truly discovered, I’d no idea that a more sophisticated version of this is how all pop music was recorded – that if I recorded a pre-set keyboard beat (funky salsa was the best) mixed with a rhythm guitar part through the Realistic, I could then play that recording back while adding more parts – keyboard, guitar, voice, whatever. I wish I still had the tapes. It wasn’t until the next decade with my high school band, Groovy Lucy’s first, and sadly, only, release, that I was able to see a real pair of kick ass Sony 8 track tape machines working in all their glory. THIS is how rock n roll is made (until a decade later when it wasn't anymore).

Into this rich petri dish of raw adolescent musical obsession and dodgy technology stepped the guitar playing of Johnny Marr. I had spent my time learning Zeppelin tunes and trying, desperately to sound like THE EDGE (fine I’ll use the name) without ever even hearing of a delay pedal, not to mention nailing Slash’s genius doodeedahdoh deedle deidle guitar part from “Sweet Child ‘o Mine”. None of these things prepared me for Marr and The Smiths. I realise that for most people Morrissey is the face of The Smiths, but for me it was all about those jangly, frenetic, tightly-constructed guitar parts. I couldn’t figure out for the life of me how some of these things were played because there was nothing in my customary hard/southern/classic rock models that prepared me for tracks like, for example, This Charming Man. Again, didn't sound so mind-blowing, until I sat down to try and play the damn thing. It is interesing to me the degree to which this sound was, when I was young, firmly in the whiteboy music category, unlike, say, the blues. The fact that it pays homage as much as anything to Ghanaian Highlife music totally escaped me. It is also important to remember, as always, that we didn’t have the internet (good GOD, how did we ever know anything?) and I never really got to see Marr playing. I only had, to use the tweed-jacket-with-elbow-patches term, the sound object. What I didn’t get was that the crude hard down-scrape picking motion that was so good for mimicking the attacks, bends, and hammer-ons/offs of Jimmy Page solos, or banging out palm-muted rhythm guitar parts for everything from The Cars to Megadeath, were actually comparatively simple even if they sounded all aggressive and flashy. Marr’s playing crossed strings nimbly in a way that didn’t seem like a big deal, but was actually stunning. I thought he was a finger picker – it’s the only way! But no, he is just exceptionally good with a plectrum, which can be easily seen now that we do have the internet. This right-hand skill was in a way more impressive, even, than the athletic playing of folks like Kirk Hammett (Metallica) and Alex Lifeson (Rush), who I would soon be avidly trying to emulate. I just could never manage Johnny Marr, which is the sole and completely justifiable reason why I think he’s an asshole.

From there I retreated to other more manageable guitar styles. Stan Cullimore’s playing for The Housemartins offered all the jangle of Johnny Marr without the impossible-to-fucking-play-ness. But it was the straightforward rocky/melodic stylings of Robert Smith and Porl Thompson from The Cure’s guitar-driven tracks that my first true, Pete Townshend-esque, glorious, parents not home, Peavy turned to 10, standing-on-the-bed-with-a-severe-white-man’s-overbite moment. It was “Push” from The Cure’s Head on the Door album, which is (for you guitarists) a truly satisfying use of a melodic line played against open, palm-muted strings. It’s a similar yet more sophisticated version of the technique found in Peter Buck’s guitar part on “Seven Chinese Brothers/The Voice of Harold”. BTW those two tracks deserve a blog entry in themselves, but I’m talking about The Cure just now, so, that brings me too…

Early puberty: floppy hair hides my feelings

My only available childhood examples of English Male-ness were Morrissey, Ian McCullogh, Robert Smith, and Magnum P.I.'s butler, Higgins (R.I.P. John Hillerman, 1932-2017). English men are all like these people, right? Robert Smith, who to my mind was always a kind of hairsprayed English Bobcat Goldthwait in high tops, offered an enviting alternative to macho classic and southern rock dudes on the one hand, and the picture-perfect model types – George Michael and the like – on the other. I guess this is what genuine “alternative” was before it became so overused as to be meaningless. Yet, it’s important to remember that 80s right-of-the-pond bands like The Cure, U2, Joy Division, The Psychedelic Furs, Simple Minds, Echo and the Bunnymen, Pulp and many more emerged from the same late 70s primordial post punk soup. A large chunk of what ended up being called alternative by the late 80s was simply music that managed to be, in some cultural context or another, counter to that particular attendant mainstream, and the while the whole idea of underground or DIY music (a term used more in the cultural context in America – nothing to do with redoing your kitchen) existed, it was not to my mind treated as a style at that point, at least not in the way that punk had been a decade earlier in Britain. But in truth, most styles are defined by what they are not as much as what they are, remembering that Grunge brings Pearl Jam, Nirvana and Soundgarden immediately to mind despite the fact that these bands are rather divergent in terms of actual stylistic traits. Same goes for post punk, and certainly for what became "alternative".

It’s important to note, then, that alternativeness can take on many forms, and I think, though I didn’t understand at the time, that it was important for me to encounter alternative forms of sexuality when I was young. Musical style isn’t just about how music sounds, but what attitude music presents. I have a brilliant, sexual-politics-savvy wife to thank for enabling this perspective. So yeah, The Cure, and adolescent sexuality. Disclosure time! Woo! Honestly, I can’t overstate the role that this music had in mitigating the worst effects of my religious upbringing. Everyone in my immediate community stressed the absolute necessity for voluntary celibacy before marriage, and all rock n’ roll could give me was “Hey hey momma with the way you move, gonna make you sweat, gonna make you groove…” Making people sweat and groove was fine, so long as it was ONLY WITH A LIFELONG MATE ALREADY CEREMONIALLY ORDAINED BY GOD AND HIS CHURCH FOR THE RAISING OF CHRISTIAN CHILDREN, AMEN. Absent any healthier models for sweating and grooving, The Cure’s version of bashful romanticism was like, to use the religious metaphor, manna from heaven. “Hey hey momma with the way you move, gonna stand in the corner at the middle school dance hiding behind floppy hair and think about you a lot and stare at you in math class because I think you’re wonderful.” Not great, but decidedly better. And there was no better way to spend Sunday afternoon, after church, than perusing my school annual with Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me on the turntable. God, being a teenager was damnable.

The tracks “Catch”, “One More Time”, “Just Like Heaven”, “The Perfect Girl”, and “A Thousand Hours” all contained a kind of male longing that didn’t present a sexist violent subtext, even if they did present annoyingly maudlin self-obsession as the alternative, which experience has taught me is still one of the myriad of ways that dudes like me can express their sexist prickishness. Again, better, but not great. I think I really needed these kinds of songs though, because you know, it actually was hard being a horny teen amongst all these beautiful, healthy, unattainable teen bodies. The New Romantic alternative to macho rock n roll, flawed though it was, offered small reminders that these unattainable teen bodies were, more importantly, people, who were worthy of admiration rather than only my desire. Again, putting women on a pedestal is yet another way of denying them an essential humanity, but it’s probably better than seeing them as subservient sex objects. I think that through all this, even today I’m not the best relationship-haver – I think I got there in the end, to use a phrase (and I got the whole life-mate thing sorted, and she’s a damn peach, let me tell ya!) – but I do think The Cure in part saved me from trending toward something darker as an adolescent. Thanks, fellas.

Next up – as we approach the 90s

I’m going to wrap this entry up. Next time I get around to this, I’ll explore more in depth the albums released in ’88, then ’89, ’90 and beyond. We’ll see how far I get. I think it is going to be a weird ride, for me, and for the two or three people who might read it. Being a teen was monstrously hard, as much as I miss some aspects of it. But music. Music made it bearable somehow. It enframed my adolescence, chiming in with the meaning of everything, be that religion, sex, anger, hurt, or even love. It also generated meaning, changed me as I changed. And I don’t want to stop changing until I die. I want to stay credulous to all this music as I get old. Digging into my adolescent pop music experiences may seem an odd way to do this, but it has the effect of reminding me that this life-enframing and life-changing continues happening even now, but only if I make it happen, have the discipline to continue to engage as I get older, and resist the temptation to place my emotional centre on ‘back in the day’ music. And pulling apart these memories above all reminds me of this one essential point: I came to all this music as a child, unsuspecting, fresh, and it was only in the encounter that meaning was forged, and in that forging is where the musical life is lived. The best recent example of this as an adult came in 2012, with the death of my dearly beloved Uncle David, and, somewhat arbitrarily, the band First Aid Kit. That Lion’s Roar album had come out, and my wife and I listened to it a lot through the summer of that year. I found it interesting – it’s weird when non-Americans start sounding more American than the Americans – but it didn’t have that deep, cut-to-the-core meaning for me. It does now, not because of the music itself, but because it was the soundtrack to the sudden and devastating loss of a loved one. I can’t listen to that album any more without “hearing”, emotionally, that loss.

Hmm, ending time. Eh, Um. I don’t want to get smarter, sexier or richer, really, though the latter would help. But I do want to get better, or more at peace, and like it or not that for me has as much to do with music as anything. God, what a weird life to have ended up with. Why this, why music!? …well, I suppose, why not? (I HATE ending stuff like this, because everyone, good writers, bad writers, anyone who’s ever tried to write with meaning, feels compelled at this point to “pinch off the loaf” as it were, with a nice, quippy ending. [plop… flush] I’ll approach it with snide mockery, if you don’t mind. Every day with the MAGIC of POP MUSIC is an ADVENTURE, kids. All you gotta do is jump on in that deep end, ONE, TWO, THREE…)

The funny thing is, I really believe that.